Well, the weekend started on a bit of a high. The brother came up and we both set off to the Odyssey Arena to see REM in concert. And very good they were too. We arrived pretty late, an hour late in fact, but I think the band had only been on stage 20 minutes or so.

At first, things seemed at little dead. The people sitting in the posh bits were staring at the stage like a convention of restaurant critics. I wondered if they were dead. And the band were doing all their new stuff which I'm ashamed to say I don't know at all. We did question whether we should just set off for the bar. But it's a good thing that we stayed.

Things hotted up once REM moved onto Orange Crush. All of a sudden everyone was dancing, even the people in the seats, and Michael Stipe started buzzing, and then it was brilliant. They went through a few of the classics and some of their more upbeat new stuff.

The brother was commenting on how relaxed Stipe is on stage and it's true: once there was some feedback from the crowd, he was amazing. He chatted away and danced and generally ran about in a rock-starrish fashion. And the music really flew. Especially, to my REM-amateur's mind, Losing my Religion.

Just as a quick aside, one other thing the brother noticed was the amazing pride of people in Belfast. Every time the city was mentioned, the placed erupted into a frenzy: great to hear, especially given my general pessimism about a feeling of shared space in NI.

Anyway, I'm off down in Dublin for the weekend, seeing the folks, visiting friends and, on Monday, doing a spot of library work. More blogging upon my return home.

Saturday, February 26, 2005

Friday, February 25, 2005

Sceptered Isles

There was an interesting review of the new Oxford Dictionary of National Biography in last week's London Review of Books. The DNB is an enormous project, including as it does over 50,000 biographies, with the criteria for entry being that one must be dead and that one must have "in some way influenced the nation's life."

The review makes for an interesting read and I fully recommend it, but I was especially struck by Stefan Collini's comments on nationalism. The original DNB, apparently, was regarded as emphasising "the familiar truths of national character." "Less fortunate nations," Collini continues,

The current DNB also reveals some interesting things about nation. But which nation? Collini refers to "this particular north-west European archipelago," but it's hard to see how this sits with the idea of a singular nation (I can count five nations in the archipelago, but the Cornish might suggest that there are six). But let's not get freaked about questions of territorial independence or about the position of Irish nationalism in all this. Instead, let's just assume that the DNB is referring to the British nation. But this in itself provokes some interesting thoughts.

First, the inclusive enterprise of the DNB suggests something about the idea of the British nation. That is, Britain is timeless. If one looks at Irish, or German, or American nationalism, one sees a story of a project. The nation has foundational moments and though (especially with the Irish) there are references and incorporations from the distant past (Newgrange, etc.), the story of the nation is a story of nation-building. And of state-building.

For Britain (and maybe France, though I'm not so sure), the nation is more or less unchanging. Sure, Elizabethan England saw the foundation of the modern state, but the general story is that, since the Romans arrived, England (and ergo Britain) has been stable, independent and unchanging. Of course, it's bollocks, partly because the story of England is far more complicated than that and partly because the melding of England and Britain is not at all a simple process.1 But that's the story.

I'm reminded, just to take a slight detour, of the idea of Oxford in Phillip Pullman's His Dark Materials trilogy (though I only read the first one, which is set 'in a world much like our own, but different in many ways' so I can't speak for his other books). For Lyra, Oxford acts as a nest, almost. The colleges are timeless, unchanging, almost in stasis, and though the town is riven with distinctions of class, all children gather together in defiance of outsiders. There are also scary hidden depths that Lyra encounters briefly, but they can be easily avoided.

Anyway, it strikes me that the DNB can appeal to the idea of Britain as the neutral medium upon which events unfolded, the stable order upon which the pursuit of knowledge or of happiness or whatever, was founded. The biographies contained within don't tell the story of a communal project, of an endeavour towards a common end, but merely of character, of individuality, of the person flourishing (mostly) in the comfort of the national home.

How different from the mirror nationalisms on this island, replete as they are with stories of foundation (1916, the Solemn League and Covanent) and with claims to cultural homogeneity (often in terms of one's priority over the other). One would imagine that 'influence on the life of the nation' might be defined far more narrowly for the Irish nationalisms than for the idea of Britishness (though that said, I was fascinated by this little snippit over on ATW).

Which raises one final question: this Britishness thing. One of the great clichés of Northern Ireland is that Unionists are the only British nationalist in Britain. Well, in one sense it's true, given that Unionism has a pretty unique relationship to the idea of, well, the Union (borne, I would suggest, from their being the only group in Britain who don't take their place in the Union for granted. Au contraire). But I think that people also say this because the only nationlisms they recognise tend to be the more truculant 'ethnic' nationalisms in the Irish mould. And Unionism is certainly (though by no means necessarily) replete with religious and cultural talk.

But of course there is a British nationalism, upon which projects like the DNB are founded. For most of the other nationalisms in the UK, this British nationalism is just not a problem. It's a state patriotism that can sit quite comfortably with ethnic nationalisms, provided they acknowledge the state.

The really weird nationalism in the UK is of course that of the English. The English certainly do have a habit of conflating Britishness and Englishness, of not seeing any distinction between the two, but I'm quite sympathetic with this. The English story is very difficult, in part because it is the story of Britain as a whole. The English problem, I'd suggest (briefly: work beckons!), is not strictly arrogance, but rather that, outside Britishness, Englishness barely exists.

1 This is more or less the theme of Norman Davies's The Isles.

The review makes for an interesting read and I fully recommend it, but I was especially struck by Stefan Collini's comments on nationalism. The original DNB, apparently, was regarded as emphasising "the familiar truths of national character." "Less fortunate nations," Collini continues,

in whom the spirit of liberty and energy of ‘character’ had been suppressed by centuries of tyranny and regulation, may have committed public funds to corresponding enterprises, but their progress had been slower and the outcomes less glorious. ‘Our British lexicographers,’ the Athenaeum declared in 1900, ‘have had the satisfaction of administering a handsome beating to their most formidable competitors, the Germans.’ Our dictionary had ‘trotted the distance’ in little more than half the time it had taken the initiative-lacking Teutons ‘to waddle through the alphabet’.

The current DNB also reveals some interesting things about nation. But which nation? Collini refers to "this particular north-west European archipelago," but it's hard to see how this sits with the idea of a singular nation (I can count five nations in the archipelago, but the Cornish might suggest that there are six). But let's not get freaked about questions of territorial independence or about the position of Irish nationalism in all this. Instead, let's just assume that the DNB is referring to the British nation. But this in itself provokes some interesting thoughts.

First, the inclusive enterprise of the DNB suggests something about the idea of the British nation. That is, Britain is timeless. If one looks at Irish, or German, or American nationalism, one sees a story of a project. The nation has foundational moments and though (especially with the Irish) there are references and incorporations from the distant past (Newgrange, etc.), the story of the nation is a story of nation-building. And of state-building.

For Britain (and maybe France, though I'm not so sure), the nation is more or less unchanging. Sure, Elizabethan England saw the foundation of the modern state, but the general story is that, since the Romans arrived, England (and ergo Britain) has been stable, independent and unchanging. Of course, it's bollocks, partly because the story of England is far more complicated than that and partly because the melding of England and Britain is not at all a simple process.1 But that's the story.

I'm reminded, just to take a slight detour, of the idea of Oxford in Phillip Pullman's His Dark Materials trilogy (though I only read the first one, which is set 'in a world much like our own, but different in many ways' so I can't speak for his other books). For Lyra, Oxford acts as a nest, almost. The colleges are timeless, unchanging, almost in stasis, and though the town is riven with distinctions of class, all children gather together in defiance of outsiders. There are also scary hidden depths that Lyra encounters briefly, but they can be easily avoided.

Anyway, it strikes me that the DNB can appeal to the idea of Britain as the neutral medium upon which events unfolded, the stable order upon which the pursuit of knowledge or of happiness or whatever, was founded. The biographies contained within don't tell the story of a communal project, of an endeavour towards a common end, but merely of character, of individuality, of the person flourishing (mostly) in the comfort of the national home.

How different from the mirror nationalisms on this island, replete as they are with stories of foundation (1916, the Solemn League and Covanent) and with claims to cultural homogeneity (often in terms of one's priority over the other). One would imagine that 'influence on the life of the nation' might be defined far more narrowly for the Irish nationalisms than for the idea of Britishness (though that said, I was fascinated by this little snippit over on ATW).

Which raises one final question: this Britishness thing. One of the great clichés of Northern Ireland is that Unionists are the only British nationalist in Britain. Well, in one sense it's true, given that Unionism has a pretty unique relationship to the idea of, well, the Union (borne, I would suggest, from their being the only group in Britain who don't take their place in the Union for granted. Au contraire). But I think that people also say this because the only nationlisms they recognise tend to be the more truculant 'ethnic' nationalisms in the Irish mould. And Unionism is certainly (though by no means necessarily) replete with religious and cultural talk.

But of course there is a British nationalism, upon which projects like the DNB are founded. For most of the other nationalisms in the UK, this British nationalism is just not a problem. It's a state patriotism that can sit quite comfortably with ethnic nationalisms, provided they acknowledge the state.

The really weird nationalism in the UK is of course that of the English. The English certainly do have a habit of conflating Britishness and Englishness, of not seeing any distinction between the two, but I'm quite sympathetic with this. The English story is very difficult, in part because it is the story of Britain as a whole. The English problem, I'd suggest (briefly: work beckons!), is not strictly arrogance, but rather that, outside Britishness, Englishness barely exists.

1 This is more or less the theme of Norman Davies's The Isles.

Thursday, February 24, 2005

Belfastian Cold

The fact that I keep posting photos suggests that my creative humours are being soaked up elsewhere, specifically on a long-overdue article. But here's something to fit with the Wintry air of the day, and with Andrew McCann's very amusing rant over on ATW. Suffice to say, when I took this photo it was -10oc. Strangely, though, I was warmer then, standing on a bridge between Stockholm proper and Djurgården, than when I was walking into work this morning.

Golden Gates

The net is replete (also here) with photos of Christo and Jean-Claude's installation, The Gates in Central Park, New York. I'm a big fan of this sort of art, where the environment, whether natural or man-made, is an integral (and unpredictable) component of the work (cf. Andy Goldsworthy).

My favourite photo of The Gates, which sets the work not just in Central Park, but in a very Wintry Manhattan, is here.

My favourite photo of The Gates, which sets the work not just in Central Park, but in a very Wintry Manhattan, is here.

Wednesday, February 23, 2005

Bridges

Not much going on in my brain today. So here's a picture instead. Mel mentioned it a little while ago, and it is one of my favourite (if I say so myself) photos. It's of a bridge across the Columbia River in Portland, Oregon this time last year. The grey day heightened the colour of the bridge, and the bird in the middle just completes it for me...

Tuesday, February 22, 2005

Rée on Deaf Nationalism

I'm reading (on and off) Jonathan Rée's I see a Voice at the moment. It's not as clear as I'd like, but makes for an interesting archeology of sign language and cultural responses to the deaf. Anyway, he has a rather interesting article on deaf nationalism in this month's Prospect Magazine. I've wanted to write an article about deaf identity and intergenerational justice for a while but, as with so many things, it remains on the 'to do' list. I'm not sure I'd write in Rée's style, but I think I'd start from the same concerned standpoint that he does.

Series of Unfortunate Events (for SF)

Saturday's Irish Times carried an article (subs required) by Mark Brennock reviewing the latest shenanigans between the Irish Government and Sinn Féin. It's a pretty good analysis, and though it probably won't tell you much that's new, it's well worth the read, so I thought I'd post it here.

Is the party over?

Irish Times (Dublin, Ireland)

February 19, 2005

Following this week's extraordinary events, there seems no way back to normal political discourse for Sinn Fein until the question of IRA criminal activity has been resolved, writes Mark Brennock , Chief Political Correspondent

Gerry Adams flew home from Bilbao yesterday afternoon into the biggest crisis facing what he calls the republican movement. Minister for Justice, Michael McDowell calls it the provisional movement, not wanting to surrender the title of republican to Adams's organisation. The crisis for Adams is that when McDowell called this movement a "colossal crime machine" on radio yesterday, he will have been believed by more people than ever before.

The Government has led a two-month rhetorical onslaught on Adams's movement for its refusal to leave violence and criminality behind, seven years after the signing of the Belfast Agreement. In parallel, the IRA has carried out a series of actions that could not have been better planned or timed to prove the Government's point.

Adams arrived home from his book promotion tour yesterday to a leadership floundering as it attempts to come to terms with a political environment that has changed utterly in just two months. It faces pressure from above and below.

The Government - aided ably by the IRA itself - has severely damaged the veneer of political respectability that Sinn Fein has so carefully created over the past decade. Meanwhile, in Belfast, IRA members killed a party supporter Robert McCartney in an act of murderous thuggery, before threatening witnesses to shut them up. The anger from within its own community has shaken the republican movement severely.

The sudden crisis has caught the movement by surprise. After all, since the peace process began, IRA killings, beatings, shootings, robberies and money-laundering have continued in parallel with political developments and nobody has seemed to mind all that much. Last December Sinn Fein was on the verge of yet another "historic" deal, this time one that would have put it in government with Ian Paisley's DUP and would have put its members on police boards. Nobody in the Government was denouncing it as a criminal mob then.

But now there is no way back into normal political discourse until the question of IRA activity has been resolved. Until recently, Sinn Fein had hoped that its candidate, Joe Reilly, could challenge for a Dail seat in the forthcoming Meath by-election. Now it must fear a demoralising slump in support in the wake of its worst period of publicity in a decade. The same concerns apply in relation to the British general election in May. For years there has been a sense that Sinn Fein would destroy the SDLP electorally. Now, within the SDLP, there is some hope that the attention being paid to the ongoing IRA criminal activity will remind nationalist voters why a large majority of them voted SDLP rather than Sinn Fein before the peace process began.

As he prepared to leave Bilbao yesterday, there was a suggestion in Adams's remarks that we are at a major watershed in the history of the peace process. He said he was "coming home to deal with the situation". He had asked for a full report to be ready for him.

Asked on RTE's News at One yesterday what would happen if evidence emerged that the IRA had, after all, carried out the Northern Bank raid, he said this would "take very serious reflection by me and others who are in the leadership of Sinn Fein". He said he did not want to be tainted with criminality: "I don't want anybody near me who is involved in criminality. I will face up to all of these issues if and when they emerge."

Asked whether that meant he would walk away from "certain people" if presented with proof of an IRA connection with the Northern Bank robbery he said: "We will weather the storm and I will not walk away from any challenge which presents itself in the time ahead. If Sinn Fein has issues to deal with, we will deal with those issues." This, of course, could mean something or nothing. At most it could mean he recognises that Sinn Fein must "deal with" its relationship with violence and criminality once and for all, possibly breaking ranks with those who want to continue with such activity. At its least, it could simply mean that Adams was seeking to say something that sounded interesting but was essentially meaningless in response to a tricky question.

McDowell made it clear yesterday that he believed it was the latter. Don't be fooled by talk of splits and divisions, he said. The movement is coherent and united under a single leadership.

The new situation is so shocking for the republican - or provisional - movement because it was completely unexpected. It is behaving more or less according to the same pattern as it has done since the peace process began. The ceasefires saw an end to the killings of police, soldiers and others seen as "legitimate targets", and the bombing campaign in the North and Britain in the struggle against the British occupation. But other activity - robberies, extortion, "punishment" attacks and murders of alleged petty criminals and internal dissenters continued.

Such occurrences were much less frequent than before the ceasefires, but they were regular. However, those who wrote about such activity and drew attention to it were denounced as peace process saboteurs.

In July 1998, just three months after the Belfast Agreement was signed, the RUC said the IRA had shot dead Andy Kearney in Belfast. The following year the FBI disrupted an IRA gun-running operation in Florida, and three men were subsequently jailed. The then Northern Secretary, Mo Mowlam, said she accepted security advice that the IRA shot dead Charles Bennett in July 1999. The killings of Belfast drug dealer Edmund McCoy in May 2000 and of Joe O'Connor in October 2000 were blamed on the IRA.

In August 2001 came the arrest of the Colombia Three. In October 2002 Daniel McBrearty was shot dead in Derry - another killing blamed on the IRA.

On and on it went, with talks that made breakthroughs and talks that broke down. The executive was formed, suspended, re-formed and suspended again. Acts of weapons decommissioning took place out of public view. The sense was of a political process inching forward slowly but going in the right direction. While nasty incidents took place regularly in different parts of Northern Ireland, these were tolerated as inevitable blips during what was believed to be a total transition of an armed and violent organisation with a political wing into a political party which had left behind its violent history. In the meantime, the Government made little fuss about the regular IRA actions. The policy was one of "constructive ambiguity" in which the parallel lives of the movement were tolerated in the hope that this was simply a transitional phase on the road to a total end to violence and criminality.

Sometimes, the illegal and legal elements of the movement's activity cohabited in the same building. In November 2002, the PSNI uncovered an IRA spying operation at Stormont.

In May 2003 it said Armagh man Gareth O'Connor, who had been abducted and disappeared, was an IRA victim. The PSNI Chief Constable, Hugh Orde, reported some intimidation of members of District Policing Partnerships later that year. In December, 2003, the Garda and the PSNI said the hijack of a truck, carrying cigarettes worth about €1.6 million, had all the hallmarks of an IRA operation.

On it went into last year. Orde said the IRA was responsible for an alleged abduction of dissident republican Bobby Tohill (47) in Belfast city centre and for punishment beatings. In November, as hopes remained for a historic power-sharing deal involving Sinn Fein and the DUP, the Independent Monitoring Commission reported that the IRA was making millions of pounds from robberies and smuggling in the North.

The commission relies heavily on information from the security forces both sides of the Border, and this information is in turn provided to the two governments. It blamed the IRA for a multimillion pound robbery of goods from the Makro store in Dunmurray in May 2004. Up to the end of September 2003 republicans were blamed for 52 "punishment" shootings; to the end of last September republicans were accused of 22 such shootings. A political associate of Aengus O Snodaigh TD, Niall Binead, was convicted of IRA membership late last year and evidence was heard of a spying operation on politicians in the Republic.

In short, the IRA has been carrying on like this for years. But in December, the Government's tolerance ran out. The Government was both disappointed and angry at the failure to reach a comprehensive deal before Christmas. Until close to the end of negotiations, those talks were believed to be foundering on the sole issue of whether IRA decommissioning should be photographed or filmed. Indeed, when Michael McDowell announced there was a second issue - the IRA's failure to sign up to a pledge not to engage in criminal activity - there was initial scepticism over whether this was as big an issue as he was making out.

This marked the start of the Government's turn against the republicans, and the end of the policy of constructive ambiguity. Displaying an impressive grasp of republican theology, McDowell announced to a surprised public that the IRA did not believe any of its actions were capable of being seen as criminal, because it was the IRA and therefore the legitimate government of the Republic. The scepticism did not last long, however. Adams indicated on television that this was indeed the position. Then McDowell got Mitchel McLaughlin to admit on television that he did not see the revolting killing in 1972 of Jean McConville, mother of 10, as a crime.

No sooner had the talks on the decommissioning and crime issues broken down in December than the IRA lifted GBP26.5 million from the Northern Bank in Belfast. The persistence with which the Taoiseach asserted that the Sinn Fein leadership knew about this robbery in advance, and had therefore behaved duplicitously during the failed talks, deeply angered Adams and Martin McGuinness.

Then came the stabbing to death of Robert McCartney in a Belfast bar, believed to have been done by IRA members. The dead man's family, Sinn Fein supporters all, laid into the IRA for allegedly intimidating witnesses and said those with information should go to the PSNI. Pitted against the family of a man killed by IRA members, Sinn Fein backed off its usual line of refusing to say people should cooperate with the police. If people saw the PSNI as a "respectable" body, they could go to it, said Adams.

And now comes this major money-laundering operation, apparently with Sinn Fein members' fingerprints - perhaps literally - all over it. All that is required to complete the linkage between Sinn Fein, the IRA and the Northern Bank robbery - and to make liars or fools of the Sinn Fein leaders who insisted they believed IRA denials - is confirmation that some or all of the money seized over the past three days was stolen from the Northern Bank.

There is no going back to the twin-track strategy now. Sinn Fein has five TDs and three MEPs, and it is the largest nationalist party in the North. A refusal to end IRA activity might not cause huge electoral damage in the North. It hasn't damaged it in the Republic in recent years, but it would almost certainly do so now.

The extraordinary recent events promise to leave no doubt that Sinn Fein and the IRA are, as the Taoiseach says, "two sides of the same coin". They will show that the movement, whatever you choose to call it, is involved in major criminal activity and has no plans to stop. It must be likely that in time, at least one of the 20 people involved in the Northern Bank robbery will be caught and IRA involvement will be established. And continuing money-laundering investigation will surely lead to the doorsteps of prominent figures in the IRA and Sinn Fein.

It will not then be credible for Sinn Fein to deny involvement in various criminal acts, or to dismiss those acts as isolated or unauthorised incidents carried out by rogue elements. At that point, if it is to have a political future, the republican, or provisional, movement will have to have something new to say.

Is the party over?

Irish Times (Dublin, Ireland)

February 19, 2005

Following this week's extraordinary events, there seems no way back to normal political discourse for Sinn Fein until the question of IRA criminal activity has been resolved, writes Mark Brennock , Chief Political Correspondent

Gerry Adams flew home from Bilbao yesterday afternoon into the biggest crisis facing what he calls the republican movement. Minister for Justice, Michael McDowell calls it the provisional movement, not wanting to surrender the title of republican to Adams's organisation. The crisis for Adams is that when McDowell called this movement a "colossal crime machine" on radio yesterday, he will have been believed by more people than ever before.

The Government has led a two-month rhetorical onslaught on Adams's movement for its refusal to leave violence and criminality behind, seven years after the signing of the Belfast Agreement. In parallel, the IRA has carried out a series of actions that could not have been better planned or timed to prove the Government's point.

Adams arrived home from his book promotion tour yesterday to a leadership floundering as it attempts to come to terms with a political environment that has changed utterly in just two months. It faces pressure from above and below.

The Government - aided ably by the IRA itself - has severely damaged the veneer of political respectability that Sinn Fein has so carefully created over the past decade. Meanwhile, in Belfast, IRA members killed a party supporter Robert McCartney in an act of murderous thuggery, before threatening witnesses to shut them up. The anger from within its own community has shaken the republican movement severely.

The sudden crisis has caught the movement by surprise. After all, since the peace process began, IRA killings, beatings, shootings, robberies and money-laundering have continued in parallel with political developments and nobody has seemed to mind all that much. Last December Sinn Fein was on the verge of yet another "historic" deal, this time one that would have put it in government with Ian Paisley's DUP and would have put its members on police boards. Nobody in the Government was denouncing it as a criminal mob then.

But now there is no way back into normal political discourse until the question of IRA activity has been resolved. Until recently, Sinn Fein had hoped that its candidate, Joe Reilly, could challenge for a Dail seat in the forthcoming Meath by-election. Now it must fear a demoralising slump in support in the wake of its worst period of publicity in a decade. The same concerns apply in relation to the British general election in May. For years there has been a sense that Sinn Fein would destroy the SDLP electorally. Now, within the SDLP, there is some hope that the attention being paid to the ongoing IRA criminal activity will remind nationalist voters why a large majority of them voted SDLP rather than Sinn Fein before the peace process began.

As he prepared to leave Bilbao yesterday, there was a suggestion in Adams's remarks that we are at a major watershed in the history of the peace process. He said he was "coming home to deal with the situation". He had asked for a full report to be ready for him.

Asked on RTE's News at One yesterday what would happen if evidence emerged that the IRA had, after all, carried out the Northern Bank raid, he said this would "take very serious reflection by me and others who are in the leadership of Sinn Fein". He said he did not want to be tainted with criminality: "I don't want anybody near me who is involved in criminality. I will face up to all of these issues if and when they emerge."

Asked whether that meant he would walk away from "certain people" if presented with proof of an IRA connection with the Northern Bank robbery he said: "We will weather the storm and I will not walk away from any challenge which presents itself in the time ahead. If Sinn Fein has issues to deal with, we will deal with those issues." This, of course, could mean something or nothing. At most it could mean he recognises that Sinn Fein must "deal with" its relationship with violence and criminality once and for all, possibly breaking ranks with those who want to continue with such activity. At its least, it could simply mean that Adams was seeking to say something that sounded interesting but was essentially meaningless in response to a tricky question.

McDowell made it clear yesterday that he believed it was the latter. Don't be fooled by talk of splits and divisions, he said. The movement is coherent and united under a single leadership.

The new situation is so shocking for the republican - or provisional - movement because it was completely unexpected. It is behaving more or less according to the same pattern as it has done since the peace process began. The ceasefires saw an end to the killings of police, soldiers and others seen as "legitimate targets", and the bombing campaign in the North and Britain in the struggle against the British occupation. But other activity - robberies, extortion, "punishment" attacks and murders of alleged petty criminals and internal dissenters continued.

Such occurrences were much less frequent than before the ceasefires, but they were regular. However, those who wrote about such activity and drew attention to it were denounced as peace process saboteurs.

In July 1998, just three months after the Belfast Agreement was signed, the RUC said the IRA had shot dead Andy Kearney in Belfast. The following year the FBI disrupted an IRA gun-running operation in Florida, and three men were subsequently jailed. The then Northern Secretary, Mo Mowlam, said she accepted security advice that the IRA shot dead Charles Bennett in July 1999. The killings of Belfast drug dealer Edmund McCoy in May 2000 and of Joe O'Connor in October 2000 were blamed on the IRA.

In August 2001 came the arrest of the Colombia Three. In October 2002 Daniel McBrearty was shot dead in Derry - another killing blamed on the IRA.

On and on it went, with talks that made breakthroughs and talks that broke down. The executive was formed, suspended, re-formed and suspended again. Acts of weapons decommissioning took place out of public view. The sense was of a political process inching forward slowly but going in the right direction. While nasty incidents took place regularly in different parts of Northern Ireland, these were tolerated as inevitable blips during what was believed to be a total transition of an armed and violent organisation with a political wing into a political party which had left behind its violent history. In the meantime, the Government made little fuss about the regular IRA actions. The policy was one of "constructive ambiguity" in which the parallel lives of the movement were tolerated in the hope that this was simply a transitional phase on the road to a total end to violence and criminality.

Sometimes, the illegal and legal elements of the movement's activity cohabited in the same building. In November 2002, the PSNI uncovered an IRA spying operation at Stormont.

In May 2003 it said Armagh man Gareth O'Connor, who had been abducted and disappeared, was an IRA victim. The PSNI Chief Constable, Hugh Orde, reported some intimidation of members of District Policing Partnerships later that year. In December, 2003, the Garda and the PSNI said the hijack of a truck, carrying cigarettes worth about €1.6 million, had all the hallmarks of an IRA operation.

On it went into last year. Orde said the IRA was responsible for an alleged abduction of dissident republican Bobby Tohill (47) in Belfast city centre and for punishment beatings. In November, as hopes remained for a historic power-sharing deal involving Sinn Fein and the DUP, the Independent Monitoring Commission reported that the IRA was making millions of pounds from robberies and smuggling in the North.

The commission relies heavily on information from the security forces both sides of the Border, and this information is in turn provided to the two governments. It blamed the IRA for a multimillion pound robbery of goods from the Makro store in Dunmurray in May 2004. Up to the end of September 2003 republicans were blamed for 52 "punishment" shootings; to the end of last September republicans were accused of 22 such shootings. A political associate of Aengus O Snodaigh TD, Niall Binead, was convicted of IRA membership late last year and evidence was heard of a spying operation on politicians in the Republic.

In short, the IRA has been carrying on like this for years. But in December, the Government's tolerance ran out. The Government was both disappointed and angry at the failure to reach a comprehensive deal before Christmas. Until close to the end of negotiations, those talks were believed to be foundering on the sole issue of whether IRA decommissioning should be photographed or filmed. Indeed, when Michael McDowell announced there was a second issue - the IRA's failure to sign up to a pledge not to engage in criminal activity - there was initial scepticism over whether this was as big an issue as he was making out.

This marked the start of the Government's turn against the republicans, and the end of the policy of constructive ambiguity. Displaying an impressive grasp of republican theology, McDowell announced to a surprised public that the IRA did not believe any of its actions were capable of being seen as criminal, because it was the IRA and therefore the legitimate government of the Republic. The scepticism did not last long, however. Adams indicated on television that this was indeed the position. Then McDowell got Mitchel McLaughlin to admit on television that he did not see the revolting killing in 1972 of Jean McConville, mother of 10, as a crime.

No sooner had the talks on the decommissioning and crime issues broken down in December than the IRA lifted GBP26.5 million from the Northern Bank in Belfast. The persistence with which the Taoiseach asserted that the Sinn Fein leadership knew about this robbery in advance, and had therefore behaved duplicitously during the failed talks, deeply angered Adams and Martin McGuinness.

Then came the stabbing to death of Robert McCartney in a Belfast bar, believed to have been done by IRA members. The dead man's family, Sinn Fein supporters all, laid into the IRA for allegedly intimidating witnesses and said those with information should go to the PSNI. Pitted against the family of a man killed by IRA members, Sinn Fein backed off its usual line of refusing to say people should cooperate with the police. If people saw the PSNI as a "respectable" body, they could go to it, said Adams.

And now comes this major money-laundering operation, apparently with Sinn Fein members' fingerprints - perhaps literally - all over it. All that is required to complete the linkage between Sinn Fein, the IRA and the Northern Bank robbery - and to make liars or fools of the Sinn Fein leaders who insisted they believed IRA denials - is confirmation that some or all of the money seized over the past three days was stolen from the Northern Bank.

There is no going back to the twin-track strategy now. Sinn Fein has five TDs and three MEPs, and it is the largest nationalist party in the North. A refusal to end IRA activity might not cause huge electoral damage in the North. It hasn't damaged it in the Republic in recent years, but it would almost certainly do so now.

The extraordinary recent events promise to leave no doubt that Sinn Fein and the IRA are, as the Taoiseach says, "two sides of the same coin". They will show that the movement, whatever you choose to call it, is involved in major criminal activity and has no plans to stop. It must be likely that in time, at least one of the 20 people involved in the Northern Bank robbery will be caught and IRA involvement will be established. And continuing money-laundering investigation will surely lead to the doorsteps of prominent figures in the IRA and Sinn Fein.

It will not then be credible for Sinn Fein to deny involvement in various criminal acts, or to dismiss those acts as isolated or unauthorised incidents carried out by rogue elements. At that point, if it is to have a political future, the republican, or provisional, movement will have to have something new to say.

EST

I've just noticed, via last night's Late Junction, that the marvellous Esbjörn Svensson Trio have a new album out and that they'll be playing the Elmwood Hall here in Belfast on the 27th of May, followed by Vicar Street in Dublin on the 28th and the Opera House in Cork on the 29th. All the European dates are on their site.

Monday, February 21, 2005

Strange Grammar...

I've been noticing an unexpected category of person hitting this site over the last few weeks. That is, people from non-anglophone countries who have googled 'neither nor.' I suspect that I'm not quite what they're looking for but this should do the trick!

Pitt Rivers Museum

I'm having a relatively busy day, but I came across this link while I was trying to have some new thoughts. It's a virtual tour of the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, one of the many things I miss about not living in England any more. For us here in Ireland, history is most often something intangible though paradoxically always in the here and now. One of the reasons that the English often seem perplexed by this is symbolised by this wonderful room: for them history is all sorts of junk piled up together: it's an ethnology of artifacts rather than a narrative of archetypes.

The Pitt Rivers is a marvellously eccentric pile of stuff hidden in a room at the back of the University's Natural History Museum. The collections are hugely important, but the aesthetic heart of the place is in its seeming chaos. Like England itself, it's an imperial junkyard, and all the richer for it.

The Pitt Rivers is a marvellously eccentric pile of stuff hidden in a room at the back of the University's Natural History Museum. The collections are hugely important, but the aesthetic heart of the place is in its seeming chaos. Like England itself, it's an imperial junkyard, and all the richer for it.

Sunday, February 20, 2005

Afghanistan

Pankaj Mishra has an interesting article on the state of play in Afghanistan in the current issue of the New York Review of Books. His basic line is that the place is an unstable mess, in part due to mistakes in American policies and tactics.

I think his most interesting section is on drugs, describing as he does why it is that small farmers choose to grow opium (because they're rational economic actors, that's why) and why they are the ultimate losers in the country's political dance between drug revenues and illusory crackdowns. Meanwhile the coffers of the self-same warlords whose behaviour brought the Taliban on the country and who are now supported as government officials and as allies in the war on terror, are engorged by the revenue of the opium crop.

The end of the article hints at Karzai's seeming to be making some headway, but it is in general a rather tragic piece about a country repeatedly invaded by always invisible.

I think his most interesting section is on drugs, describing as he does why it is that small farmers choose to grow opium (because they're rational economic actors, that's why) and why they are the ultimate losers in the country's political dance between drug revenues and illusory crackdowns. Meanwhile the coffers of the self-same warlords whose behaviour brought the Taliban on the country and who are now supported as government officials and as allies in the war on terror, are engorged by the revenue of the opium crop.

The end of the article hints at Karzai's seeming to be making some headway, but it is in general a rather tragic piece about a country repeatedly invaded by always invisible.

Friday, February 18, 2005

Nearly Back in Action

Well, I've been laid up all week, with a stomach infection rendering my whole life into one long scene from The Exorcist, but I'm getting back into the swing of things today, much to my relief. One thing I didn't see this week, as reported on Wednesday by Paul over on N.Irish Magyar, was Belfast City Council's decision not to fund the St. Patrick's day Parade.

I have to say that, though the proclamations of elected representatives on the subject might not be utterly connected to the facts of any matter here, prone as they are to what I posted about at the start of this week, I did find my one St. Patrick's Day festival here a little strange. OK, there is something vaguely satisfying about the weirdness of standing in front of the Victorian monolith that is City Hall, with the Union Jack fluttering above it, watching Shane McGowen stumbling around the stage mumbling and three hundred teenagers in flourescent green afro wigs jumping up and down in front. Most people have to pay good money for that sort of vision but in Belfast you can get it for free!

But what I also found was something that I remarked on in my first post to this blog, way back in November. That is, that the celebration just came across as aggressive. At least part of the intention of the event was to mark some absolute ownership on the city centre for the day, in the same way that, like it or not, the 12th is partly about marking absolute ownership of various spaces for a few days in July. It always saddens me that Belfast, unlike all other cities I've been in, has no public event or space that everyone can attach themselves to.

On a much lighter note, although I am a member of the small minority whose boss is also a fantastic mentor, colleague and friend (one of the many joys of academic life), Young Irelander links to one of the best games I've seen in quite a while: yes folks, it's time to Whack Your Boss...

I have to say that, though the proclamations of elected representatives on the subject might not be utterly connected to the facts of any matter here, prone as they are to what I posted about at the start of this week, I did find my one St. Patrick's Day festival here a little strange. OK, there is something vaguely satisfying about the weirdness of standing in front of the Victorian monolith that is City Hall, with the Union Jack fluttering above it, watching Shane McGowen stumbling around the stage mumbling and three hundred teenagers in flourescent green afro wigs jumping up and down in front. Most people have to pay good money for that sort of vision but in Belfast you can get it for free!

But what I also found was something that I remarked on in my first post to this blog, way back in November. That is, that the celebration just came across as aggressive. At least part of the intention of the event was to mark some absolute ownership on the city centre for the day, in the same way that, like it or not, the 12th is partly about marking absolute ownership of various spaces for a few days in July. It always saddens me that Belfast, unlike all other cities I've been in, has no public event or space that everyone can attach themselves to.

On a much lighter note, although I am a member of the small minority whose boss is also a fantastic mentor, colleague and friend (one of the many joys of academic life), Young Irelander links to one of the best games I've seen in quite a while: yes folks, it's time to Whack Your Boss...

Monday, February 14, 2005

Bullshit: Now in Book Form

I see via Crooked Timber that Harry Frankfurt's marvellous article On Bullshit is now available as a book. It's a great read: basically Frankfurt defines bullshit as speaking without having any regard or concern for whether what you say is true or not. An important philosophical work for our times, methinks!

Update: More on Frankfurt, who apparently is appearing on The Daily Show, from Crooked Timber

Update: More on Frankfurt, who apparently is appearing on The Daily Show, from Crooked Timber

Sunday, February 13, 2005

Summer Evenings

It's a cold stormy day here in Belfast, and I have nothing of interest to say, so here's another strange photograph. I took this quite a while ago, about ten in the evening on Keel beach on Achill Island off the West Coast of Ireland, and have just received a matt print of it from the excellent Photobox...

Thursday, February 10, 2005

The Tories and their Bruising Days...

I know I posted on this before, but I thought I'd mention the subject again. Partly because John Major was on the Today Programme (Realplayer required) this morning talking about the latest row over the release of documents about Black Wednesday, when the UK was booted out of the ERM.

I should say: I like John Major. He sounds like a decent bloke and I think he's one of the better leaders that the Tories never had the wit to tolerate. Moreover, since he's not in power now, he's refreshingly honest about his premiership.

(An aside: why is Oliver Letwin not leader of the Tories? He was on the radio earlier in the week making a really daft argument sound personable and plausible. Whereas Michael Howard is just plain odd...)

Anyway, on the subject of Black Wednesday, Major said that, while he thought it had a detrimental effect on them, he didn't really think that the event was what damned his government. Rather, divisions over Europe and the sheer inevitability of being too long in power is what, so to speak, done them in.

Well, while the specific event may not have been crucial, it did seem to chrystalise in people's minds something about the Tories, which the party is yet to recover from. Which, perhaps, is why this furore is taking place now: if I can analyse the figures, so can the Labour strategists. I'm not sure if banging on about the day itself will help Labour (in the sense of 'reminding them about past Tory sins') but they probably figure that it can.

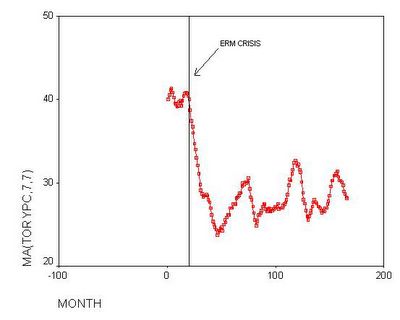

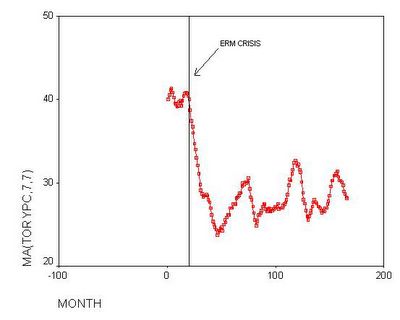

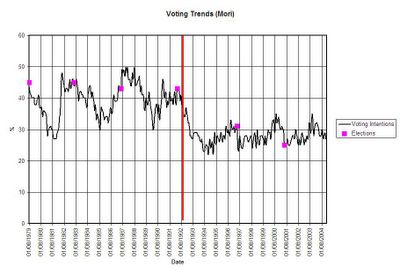

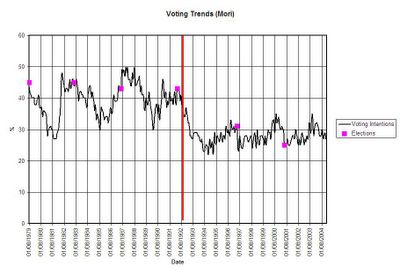

Anyway, the picture is the best response to Major's claim about Black Wednesday. My good friend John Garry, who knows all there is to know about sums, first pointed me towards this fact. And this week he did me the favour of taking the Mori data I had referred to in my last post, and tidying it up. So here is the graph for support for the Tories since Major's coming into power, using seven day moving averages:

I think that says it all...

I should say: I like John Major. He sounds like a decent bloke and I think he's one of the better leaders that the Tories never had the wit to tolerate. Moreover, since he's not in power now, he's refreshingly honest about his premiership.

(An aside: why is Oliver Letwin not leader of the Tories? He was on the radio earlier in the week making a really daft argument sound personable and plausible. Whereas Michael Howard is just plain odd...)

Anyway, on the subject of Black Wednesday, Major said that, while he thought it had a detrimental effect on them, he didn't really think that the event was what damned his government. Rather, divisions over Europe and the sheer inevitability of being too long in power is what, so to speak, done them in.

Well, while the specific event may not have been crucial, it did seem to chrystalise in people's minds something about the Tories, which the party is yet to recover from. Which, perhaps, is why this furore is taking place now: if I can analyse the figures, so can the Labour strategists. I'm not sure if banging on about the day itself will help Labour (in the sense of 'reminding them about past Tory sins') but they probably figure that it can.

Anyway, the picture is the best response to Major's claim about Black Wednesday. My good friend John Garry, who knows all there is to know about sums, first pointed me towards this fact. And this week he did me the favour of taking the Mori data I had referred to in my last post, and tidying it up. So here is the graph for support for the Tories since Major's coming into power, using seven day moving averages:

I think that says it all...

Wednesday, February 09, 2005

Regions Doing Better in Europe

I just noticed that Tom over on The Green Ribbon reports that the regions of the UK are doing better than England at influencing policy at the EU level. Having been a spectator to the admirable level of engagement with Brussels here in Belfast, this doesn't come as much of a surprise. Though the press release referred to only talks about the former, politicians and civil society groups (sometimes to the resentment of those politicians) have been instrumental in forming links with EU institutions and in forming policy here. Good stuff!

New Blogroll

I've intended to update my blogroll for a while, and today's the day! I've divided the blogs between Ireland, Philosophical/Political etc and (strangely I know) Photoblogs. The Ireland category is intended in a purely geographical sense!

Tuesday, February 08, 2005

Theban Mapping Project

I suppose if I knew how to categorise these posts, this one would go under 'very very cool sites!' Check out the Theban Mapping Project. Best if you're not on dialup and if you have hours to spare...

More on the NHS

In my previous post on the NHS I didn't propose anything positive of my own. My point in my previous post was to question the conclusions that the authors of the Reform Report arrive at: that a greater private sector involvement in cancer care would resolve the problems that cancer care faces in the UK: bureaucracy, lack of staff and lack of facilities. In this post I want to make a few remarks about funding the NHS.

Last night's Dispatches programme on Channel 4 was about the funding of the NHS. The presenter made the pretty sound case that the current funding increases for the service cannot credibly be sustained beyond 2008 and that costs are sure to rise, both because we'll have to pay back for PFI projects at high costs, because the costs of treatments are rising (I know that my own rather positive experience with NHS care probably set the country back at least £50,000) and because an ageing population will require more care. The presenter's suggestion was one that I totally support: that, given the political liability of tax increases, and if huge waiting lists are to be avoided, we'll have to move to a system of partial funding through compulsory private health insurance (paid for either by individuals or by employers) for the better off and universal, comprehensive and free-at-source care for the less well-off.

This is the system that's used across Europe, for example in France. And the French health service is marvellous. Still, the system of incentives that insurance would produce would have to be managed very carefully.

Legitimacy: First, I take it that higher income earners would have to be presented with some reason for taking on the extra burden of health insurance. Some set of incentives would have to be provided in order to make insurance worthwhile, assuming both that their taxes didn't fall and that the basic NHS care was still comprehensive. A very fine line would have to be struck. I fully support the idea that we should look at things like smaller ward sizes and, in some circumstances, faster turn-arounds for those who have assumed the costs of private insurance. Otherwise people might quite justifiably announce that they are being taxed twice for the same service.

Quality of basic provision: We'd have to be very careful, however, that we didn't head down the road the Ireland has taken: low quality basic provision, high personal costs for GP visits and costly insurance in order to be treated at a standard that's roughly equivalent to some of the services that the NHS provides now. There are unfortunate consequences at each stage of this system. The high GP costs mean that people might not present early with illnesses, meaning that they will receive less effective treatment at higher costs. The low quality basic provision is an injustice: healthcare should not be distributed based on ability to pay. And those who pay insurance should feel pretty resentful that they are not likely to see much of a return on their investment (beyond being a bit better off, in health terms, than their poorer neighbours.

I'm not sure how these pitfalls are to be avoided. I suppose the secret is that, provided the basic provision was sound, and there was real competition in the health insurance market, insurance companies might be provided with good reasons to extend a reasonable quality of care to their customers. But that would have to be achieved with a simultaneous reduction in insurance premiums, so that sufficient numbers could afford it.

What is certain is that the NHS, as is, will not last. As the presenter of Dispatches said, we have until 2008 to make up our minds. No debate on the issue means that we can expect bad decisions. Any bets?

Last night's Dispatches programme on Channel 4 was about the funding of the NHS. The presenter made the pretty sound case that the current funding increases for the service cannot credibly be sustained beyond 2008 and that costs are sure to rise, both because we'll have to pay back for PFI projects at high costs, because the costs of treatments are rising (I know that my own rather positive experience with NHS care probably set the country back at least £50,000) and because an ageing population will require more care. The presenter's suggestion was one that I totally support: that, given the political liability of tax increases, and if huge waiting lists are to be avoided, we'll have to move to a system of partial funding through compulsory private health insurance (paid for either by individuals or by employers) for the better off and universal, comprehensive and free-at-source care for the less well-off.

This is the system that's used across Europe, for example in France. And the French health service is marvellous. Still, the system of incentives that insurance would produce would have to be managed very carefully.

Legitimacy: First, I take it that higher income earners would have to be presented with some reason for taking on the extra burden of health insurance. Some set of incentives would have to be provided in order to make insurance worthwhile, assuming both that their taxes didn't fall and that the basic NHS care was still comprehensive. A very fine line would have to be struck. I fully support the idea that we should look at things like smaller ward sizes and, in some circumstances, faster turn-arounds for those who have assumed the costs of private insurance. Otherwise people might quite justifiably announce that they are being taxed twice for the same service.

Quality of basic provision: We'd have to be very careful, however, that we didn't head down the road the Ireland has taken: low quality basic provision, high personal costs for GP visits and costly insurance in order to be treated at a standard that's roughly equivalent to some of the services that the NHS provides now. There are unfortunate consequences at each stage of this system. The high GP costs mean that people might not present early with illnesses, meaning that they will receive less effective treatment at higher costs. The low quality basic provision is an injustice: healthcare should not be distributed based on ability to pay. And those who pay insurance should feel pretty resentful that they are not likely to see much of a return on their investment (beyond being a bit better off, in health terms, than their poorer neighbours.

I'm not sure how these pitfalls are to be avoided. I suppose the secret is that, provided the basic provision was sound, and there was real competition in the health insurance market, insurance companies might be provided with good reasons to extend a reasonable quality of care to their customers. But that would have to be achieved with a simultaneous reduction in insurance premiums, so that sufficient numbers could afford it.

What is certain is that the NHS, as is, will not last. As the presenter of Dispatches said, we have until 2008 to make up our minds. No debate on the issue means that we can expect bad decisions. Any bets?

Just War and Agincourt

Peter Levine has an interesting piece on Just War here. Even putting my jealousy at his erudition aside, I think I only half agree: soldiers are ultimately responsible for their own actions, but that convention is partly a (highly justifiable) response to the Holocaust. But we do know that individuals find it very difficult to override the imperatives of the organisations and groups to which they belong - organisations and groups that are not democracies in any significant sense. Will is not the sole arbiter of actions and I do wonder how much responsibility can be attributed. Anyway, Levine's post is well worth the read.

Sunday, February 06, 2005

Cancer Care in the NHS

David over on A Tangled Web, reports on a post to Civitas's blog which reports a Sunday Times article which reports on this report on cancer care in the UK, published by Reform on behalf of Doctors for Reform (as of the 7th, also reported on the BBC). The joy of hyperlinks! Anyway, I have to say that I'm always a little suspicious about independent reports that just happen to confirm the political stances of the organisations that commission them but, while I might not agree with the conclusions of the report's authors (lots more on that below), the cancer care system in the UK is certainly not responding to the injection of state cash in the manner that one might hope.1

Basically put, when the Labour government came into office, they identified a few areas that they intended to devote resources to and cancer, being a major killer, was one of them. The NHS cancer plan that was drawn up "included three major commitments:

While the first aim seems to have been achieved, I don't think the second has and, as the report at hand makes clear, the third commtment has made very little difference. The money, the authors argue, has largely been wasted. In short, "the Cancer Plan is simply not delivering as hoped and there are no reasons for expecting any dramatic improvements in the future."

Pointing out that, despite the large amount of money being pumped into cancer care, there has been no impact on death rates, the authors of the Reform report argue that

The report makes for pretty depressing reading. Essentially, government investment hasn't made much difference. Now I suspect, admittedly from my healthcare amateur's perspective, that part of the problem is that these things take time. The hiring and training of staff, especially, can be a long process. As a result, I may be less pessimistic than the report's authors on prospects for the future.2

But the report's conclusions (entitled 'The Way Forward') do trouble me.3

It seems to me that the three key words in the conclusions are choice, information and outsourcing.

I have to say that I find these suggestions somewhat strange. At least, while they may not be particularly harmful to patients, I don't see how they will improve mortality rates. Let's take them in turn:

Choice: Surely people with cancer want the most effective cure: providing them with choice entails a distinction between the most effective and less effective treatments, which doesn't strike me as denoting choice in any significant sense at all. Thankfully, the ability of patients to act upon different tastes is not at the base of the attachment to choice. Strangely, however, it's rooted in the spread of incentives and in allowing "the relative costs of different providers to be dissected." So, choice would have a national auditing function. Now, I think this is all laudible, but I suspect that it's a terribly inefficient method for providing high standards of care. Largely for reasons to do with information...

Information: The authors seem to be concerned with information, although I'm not entirely sure what they're getting at when they refer to it. I suspect that they regard informaton as being a sub-set of choice. That is, that information is provided in order for patients to make rational choices, presumably so that the market-like system can be an efficient mechanism for providing information to the state etc. But the assumptions regarding information seem optimistic. After all, the idea of rational choices based on information does depend on the literacy of patients and on the capacities of patients and their GPs to process information when under significant stress. Their choices will also be driven by a variety of actual and opportunity costs (such as the cost for a family of supporting a patient in the Royal Marsden hospital if they're from, say, Scotland. I just think that direct bureaucratic systems must be more efficient and mroe effective at supplying information without burdening either staff or patients than the market-like constructions suggested by the concept of choice.

Outsourcing: The authors' idea is that outsourcing would have a number of beneficial effects. First, it would bring extra resources into the healthcare system. Second, it would help in providing choice and, with it, higher standards. Third, it would encourage innovation. Now, I'm not hostile to private sector involvement in healthcare, provided the profit motive is not favoured over what the system should be doing, which is, well, providing people with healthcare. But, apart from what I've already said about the inadequacy of the concept of choice in this environment, I suspect, given the UK's experience with part and full privatisations, that expected efficiency gains won't manifest themselves. Instead, the state will end up paying for costs plus profits. Also, hoping for the private sector to innovate through this system is a touch naive. After all, the costs of developing new technologies are enormous and the UK would be better off devoting R&D costs directly, rather than as a side-effect of some sort of market.

Moreover, since, as the authors acknowledge, a large part of the problem is the availability of trained staff, it's hard to see how the private sector would cope with the problem. Again, it would seem that the state would be better off creating incentives in the labour market by offering radiologists etc. higher wages. The private sector is (with some exceptions) not reputed for helping like that. I'm not even sure how they might compete for existing NHS staff without increasing the costs of supply.

In short, I'm not convinced that the creation of a market for cancer care would provide the sorts of benefits that the authors envisage. I'm not entirely hostile to the idea that it might, but I don't see how there is any connection between the problems that they identify and the solutions that they suggest.

1 Although I agree that the cancer care system is not improving in line with the injection of cash, we shouldn't forget that it does do a lot of good work. 'Should do better' should not be read as 'is doing no good.'

2 My pessimism might be rooted, somewhat heartlessly, in the fact that cancer tends to hit elderly people, especially smokers (it's true that it causes 30% of deaths in those under 70, as the authors point out, but those under 70 still make up a relatively small proportion of cancer deaths). I'm not so sure that new procedures and treatments such as gene therapies will do more than what current drugs do: prolong life for a while and alleviate some suffering when people begin to die.

3 They are worth reading in full:

Basically put, when the Labour government came into office, they identified a few areas that they intended to devote resources to and cancer, being a major killer, was one of them. The NHS cancer plan that was drawn up "included three major commitments:

• To reduce the delay from referral to the beginning of treatment to two months;

• To reduce smoking in lower socioeconomic groups; and

• To invest an extra £50 million in palliative care each year from 2004.

While the first aim seems to have been achieved, I don't think the second has and, as the report at hand makes clear, the third commtment has made very little difference. The money, the authors argue, has largely been wasted. In short, "the Cancer Plan is simply not delivering as hoped and there are no reasons for expecting any dramatic improvements in the future."

Pointing out that, despite the large amount of money being pumped into cancer care, there has been no impact on death rates, the authors of the Reform report argue that

• although referrals have fallen, people are dying because of the gap between diagnosis and treatment. A study in Glasgow, for example, "found that 21 per cent of lung cancer patients became unsuitable for curative treatment during the wait for radiotherapy."

• Treatment is not as aggressive as it could be, partly because of a lack of communication of new treatments across the country and partly as a result of insufficient and unequal resource allocations.

• A lack of staffing. Although there has been an investment in facilities and in procedures, the small numbers of new staff mean that new radiotherapy machines are not being used.

The report makes for pretty depressing reading. Essentially, government investment hasn't made much difference. Now I suspect, admittedly from my healthcare amateur's perspective, that part of the problem is that these things take time. The hiring and training of staff, especially, can be a long process. As a result, I may be less pessimistic than the report's authors on prospects for the future.2

But the report's conclusions (entitled 'The Way Forward') do trouble me.3

It seems to me that the three key words in the conclusions are choice, information and outsourcing.

I have to say that I find these suggestions somewhat strange. At least, while they may not be particularly harmful to patients, I don't see how they will improve mortality rates. Let's take them in turn:

Choice: Surely people with cancer want the most effective cure: providing them with choice entails a distinction between the most effective and less effective treatments, which doesn't strike me as denoting choice in any significant sense at all. Thankfully, the ability of patients to act upon different tastes is not at the base of the attachment to choice. Strangely, however, it's rooted in the spread of incentives and in allowing "the relative costs of different providers to be dissected." So, choice would have a national auditing function. Now, I think this is all laudible, but I suspect that it's a terribly inefficient method for providing high standards of care. Largely for reasons to do with information...

Information: The authors seem to be concerned with information, although I'm not entirely sure what they're getting at when they refer to it. I suspect that they regard informaton as being a sub-set of choice. That is, that information is provided in order for patients to make rational choices, presumably so that the market-like system can be an efficient mechanism for providing information to the state etc. But the assumptions regarding information seem optimistic. After all, the idea of rational choices based on information does depend on the literacy of patients and on the capacities of patients and their GPs to process information when under significant stress. Their choices will also be driven by a variety of actual and opportunity costs (such as the cost for a family of supporting a patient in the Royal Marsden hospital if they're from, say, Scotland. I just think that direct bureaucratic systems must be more efficient and mroe effective at supplying information without burdening either staff or patients than the market-like constructions suggested by the concept of choice.

Outsourcing: The authors' idea is that outsourcing would have a number of beneficial effects. First, it would bring extra resources into the healthcare system. Second, it would help in providing choice and, with it, higher standards. Third, it would encourage innovation. Now, I'm not hostile to private sector involvement in healthcare, provided the profit motive is not favoured over what the system should be doing, which is, well, providing people with healthcare. But, apart from what I've already said about the inadequacy of the concept of choice in this environment, I suspect, given the UK's experience with part and full privatisations, that expected efficiency gains won't manifest themselves. Instead, the state will end up paying for costs plus profits. Also, hoping for the private sector to innovate through this system is a touch naive. After all, the costs of developing new technologies are enormous and the UK would be better off devoting R&D costs directly, rather than as a side-effect of some sort of market.

Moreover, since, as the authors acknowledge, a large part of the problem is the availability of trained staff, it's hard to see how the private sector would cope with the problem. Again, it would seem that the state would be better off creating incentives in the labour market by offering radiologists etc. higher wages. The private sector is (with some exceptions) not reputed for helping like that. I'm not even sure how they might compete for existing NHS staff without increasing the costs of supply.

In short, I'm not convinced that the creation of a market for cancer care would provide the sorts of benefits that the authors envisage. I'm not entirely hostile to the idea that it might, but I don't see how there is any connection between the problems that they identify and the solutions that they suggest.

1 Although I agree that the cancer care system is not improving in line with the injection of cash, we shouldn't forget that it does do a lot of good work. 'Should do better' should not be read as 'is doing no good.'

2 My pessimism might be rooted, somewhat heartlessly, in the fact that cancer tends to hit elderly people, especially smokers (it's true that it causes 30% of deaths in those under 70, as the authors point out, but those under 70 still make up a relatively small proportion of cancer deaths). I'm not so sure that new procedures and treatments such as gene therapies will do more than what current drugs do: prolong life for a while and alleviate some suffering when people begin to die.

3 They are worth reading in full:

Patients with cancer should have the same principles of choice and variety of providers that are being offered in other areas of health care. Inclusion of cancer care in national tariffs open to competitive tendering will allow the relative costs of different providers to be dissected. We could start by pilot programmes in diagnostic services and radiotherapy, with patients being offered alternative services if they experience delays. Unless opportunities for innovation are increased with appropriate incentives, health investment will be tilted into other areas and cancer care will become disadvantaged yet again.

Big improvements in access and capacity over the next two years are essential to take the momentum forward. Local private sector initiatives, in diagnosis, surgery and radiotherapy, could raise productivity appreciably in cancer centres. Open tendering would encourage a range of providers and end the block on investment and innovation. We need to improve the information available to patients on quality and access.

We are simply advocating that cancer patients should be able to benefit from the same key principles of patient empowerment, choice and competition which have been strongly advocated for the NHS by the Secretary of State. We cannot stand by and watch while such a vital area of service falls behind the rest of the NHS.

We are optimistic about the opportunities for improving use of scarce resources across cancer prevention and care. There is much that is positive about the aim of a patient–centred service with more focus on long term illness. There is much to admire about the dedication and commitment of staff in the NHS. In terms of Britain’s long term social and economic challenges, however, we believe the NHS Cancer Plan has delivered poor value for money. It is essential to search for new initiatives which will improve the situation.

For the longer term cancer services would have much to gain from a greater variety of providers. This would draw in international capital and expertise. Reliable and effective services are becoming more feasible and fundable in smaller, networked, user-friendly cancer “hotels” as well as in larger teaching centres. The professional and human commitment of staff in cancer care could be used more effectively to improve process and outcomes for many. Mortality from cancer now counts for 30 per cent of all deaths in those under 70 and 40 per cent for women. These proportions are likely to increase further as mortality from coronary heart disease reduces. Cancer patients often live in poor health unnecessarily for long periods of time due to a lack of coordination of their care by overstretched treatment services. The Cancer Networks act as cartels dividing up the workload. We need to take steps to ensure that cancer patients benefit from a greater variety of providers:

• There are new challenges in building partnerships with patients with higher levels of concern about lack of information. Cancer services have often scored unusually low in survey evidence on the quality of communication with patients. Patient Care Advisers are needed to explain the merits of different providers.

• Within two years, 30 per cent of diagnostics, radiotherapy and chemotherapy should be outsourced to the independent sector. This would drive innovation, investment and increase the quality of services provided. Such pluralism of provision would be the basis of real patient choice.

• Patients need to be involved in funding considerations with the introduction of incentives for patients not to use high cost interventions of low benefit. We need to let patients drive the agenda involving cancer experts more widely in planning for a complete financial, operational and strategic overhaul of cancer services.

• The aim should be to create an innovative culture of reform embracing private sector expertise and investment.

In the future the prevalence of cancer will rise trebling the number of people living with cancer in Britain to 3 million at any one time. This will put further pressure on process and outcomes. Even if there are increases in real funding, such numbers point to a situation in which real expenditure per patient will rise little. Sustained improvement in system performance is essential. Real improvement will not be achieved by simply giving more money to a burgeoning bureaucracy. It requires a serious commitment to reform.

Friday, February 04, 2005

Music

Indirectly via a link from a friend, I've just come across White Cholera, described on one site as a 'junk-gospel-political cabaret outfit.' Their EP is free for download, and is great fun. They've certainly been listening to far too much Tom Waits for their own good, or is it Tom Waits who's been listening to them? Oh sweet mystery...

And posting this reminds me of a link on Crooked Timber last year to Skeewiff's very frankly entitled One Sample Short of a Lawsuit (mp3), a spot of sampled Soggy Bottom Boys: great Stuff.

And posting this reminds me of a link on Crooked Timber last year to Skeewiff's very frankly entitled One Sample Short of a Lawsuit (mp3), a spot of sampled Soggy Bottom Boys: great Stuff.

Wednesday, February 02, 2005

Dawn over Belfast

I should really have been getting into work this morning, but couldn't help but pause to take a couple of photos of the dawn over Cave Hill...

Tuesday, February 01, 2005

Why the Tories Will Lose